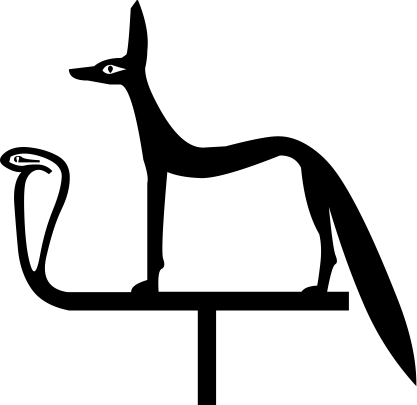

In contrast with Anubis Who is often depicted as a seated or recumbent jackal, Wepwawet most often appears as a jackal standing on all four feet 𓃥 (Gardiner E17), especially placed atop a standard that might be used in procession. The standing-jackal sign E17 should not be confused with E14, a sign used to indicate more of a domesticated canid or dog with a curled tail.

When depicted on His standard 𓃧 (E18), the platform itself may be adorned with the mysterious šdšd (shedshed) object, posited by some to be a placenta (particularly astute when comparing the ‘opening ways’ epithet to the opening of the uterus during childbirth [DuQuesne, 1995]), and/or uraeus (cobra, rearing in a protective fashion, appearing prior to the shedshed when present). In some cases, additional iconographic additions may include weaponry such as maces (the mace in particular making its first appearance from the time of King Djoser of the 3rd Dynasty) 𓃨 (E19).

Many times, Wepwawet atop His standard is shown with the tail bisecting the very end of the sledge; when rendered in fuller or larger details, we see the tail threads through a loop or fork at the end (significance unknown to this author).

In a case of very limited examples, we do see Wepwawet shown as a couchant jackal (Anubis’ signature form), sometimes atop a standard, however these incidents are isolated and rare: for example, in a late-6th-Dynasty tomb at El-Hagarsa, and an Old Kingdom stela. That being said, this mix of seated jackal imagery on the traditionally-Wepwawet standard also has instances where it is interpreted as Anubis. Overall, this form of either jackal is far more rare than any other. Meanwhile, the standard E18 and E19 Gardiner signs are also used in sparing instances to refer to the God Sed, posited to potentially be one in the same with the God Wepwawet, though nothing concrete enough exists to birth this theory into full form.

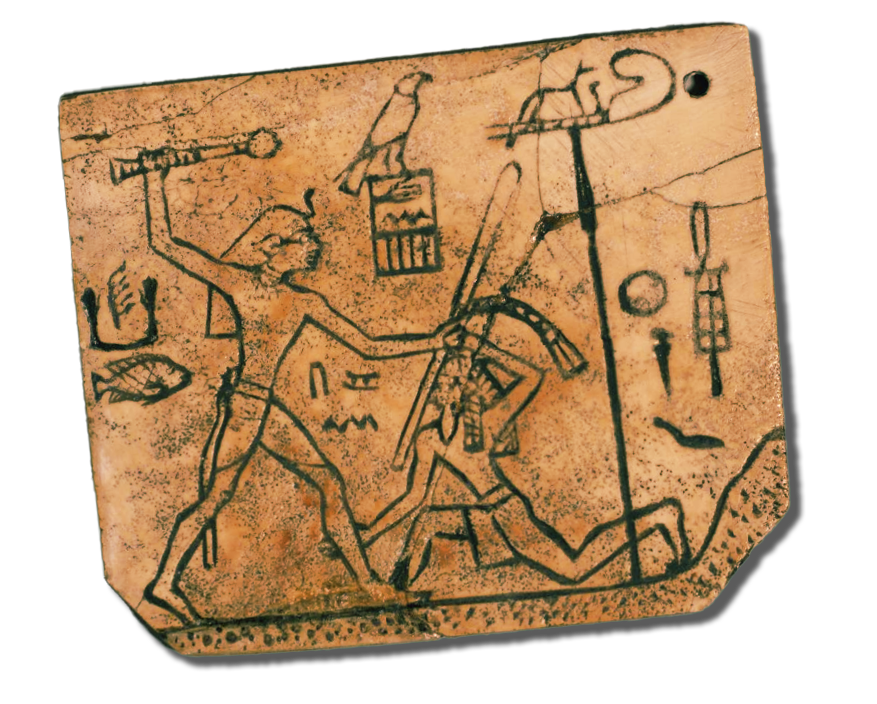

Imagery dating back to protodynastic Egypt, likely depicting Wepwawet (though some arguments are made) includes forms on palettes and mace-heads. One of the earlier depictions that could be attributed to Wepwawet on His standard is from the Bull Palette dated to Naqada III / ~3200-3000 BCE.

Of five standards, the first one and possibly the second appear to be candid, with the first having the attributes of Wepwawet on his standard. The embellishment or protuberance of the anterior standard for the initial entry could possibly be perceived to contain the shedshed object, particularly if we compare it with similar imagery in larger formats, or it could be heightened as indicative of a sledge-shape (common to Wepwawet). Note that a misidentification in the Wikipedia entry for the Bull palette notes the first two-of-five standards to be hippos.

Another early depiction which is much more clear appears on an ivory label for King Den (Dynasty I), approximately ~2985 BCE. Here we can see not only the standing jackal form, but the uraeus and shedshed objects as well. Unlike some depictions of the shedshed object, this one is becomes (perhaps by accident) visually almost an extension of the standard itself and, if drawn in small form, could easily be likened to the embellishment of the anterior standard on the Bull Palette mentioned above.

Depending on the use-case, the icon of Wepwawet-on-His-standard may be local in nature or may have a wider connotation with royalty and the sovereignty of the king.

Wepwawet continues to be depicted over the years primarily as a standing jackal including on His standard; In rare instances, a couchant jackal is seen to be representing Wepwawet, determined where the name and/or epithet of Wepwawet Himself is clearly present as opposed to Anubis. While the standing jackal tends to ring ubiquitous with Wepwawet by default, and the couchant jackal with Anubis, there are less cut-and-dry cases which can be confusing. The case (highlighted by Terence DuQuesne Jackal Divinities) of a 5th Dynasty sarcophagus in Leiden with an inscription of its owner that includes the couchant jackal, but also references the Lord of Asyut (which would normally be attributed to Wepwawet) and two contradicting epithets/statements — one common to Anubis, the other not — reminds us that there is still a lot of mystery in ancient Egypt that we may not always understand.

In addition to His animal form, He is also depicted in anthropomorphic / hybrid form (a human form with the head of a jackal, visible from as early as the 4th Dynasty), as well as in full human form (typically standing at or near the front of barques).

In Asyut, Wepwawet’s indisputable cult center, he frequently appears atop His Standard, sometimes with or without additional canids, and depictions of various ritualists and groups of officials and elites are shown worshipping this Standard in particular, which carries a heavy link to the Procession of Wepwawet. It’s important to note that in Asyut among the caches of votive stelae it was less common to see the general population depicting the mixed animal-human form which appears reserved more for those of elevated status. A breakdown of percentages and more information can be found in Eric Ryan Wells’ dissertation Display and Devotion: A Social and Religious Analysis of New Kingdom Votive Stelae from Asyut.

The form of Wepwawet most accessible to the general public was the full-Jackal / canid form. Common people were more likely to be depicted near, or even interacting with, Wepwawet’s fully-canid form, where interaction-with the canid can be seen as an act of devotion or worship (for example, offerings of cool water). Again a contrast exists between the general populace and the higher social status bracket whereby limited or no members of the elite were depicted as interacting directly with the Jackal candids in this way.

Selection of Open / Public images from The Met

Some of my personal icons of Wepwawet include: